Researchers have successfully sequenced the first genome of ancient human fossils dated to the Late Pleistocene, which was unearthed at Maludong (Red Deer Cave), Mengzi, Yunnan Province of southwestern China. The data, published July 14 in the journal Current Biology, suggests that the mysterious hominin “Mengzi Ren” (MZR) belongs to an extinct maternal branch of modern humans instead of an archaic human species previously proposed by some anthropologists, and she possessed deep ancestry that might have contributed to the origin of the first Native Americans.

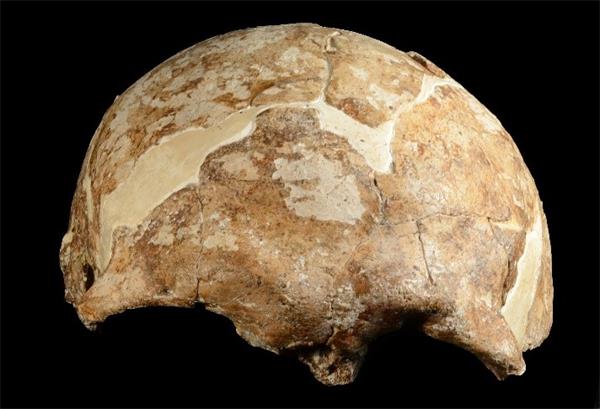

Over three decades ago, a group of archaeologists in Yunnan, China discovered the site from a quarry called Maludong where they unearthed a lot of bones including human bones. The fossils were carbon dated to the Late Pleistocene about 14,000 years ago, approaching to the period of time when modern human migrating to the New World from Asia. From the cave, researchers recovered a hominin skull cap that looked unusual. It has characteristics of both modern humans and archaic humans according to previous physical anthropological studies. For example, the shape of the skull and teeth resembled characteristics that of Neanderthals, and the brain appeared to be smaller compared with modern humans. As a result, some anthropologists had thought the skull probably belongs to an unknown archaic human species that lived until fairly recently, a hybrid population of archaic and modern humans, or the retention of a large number of ancestral polymorphisms in ancient modern human populations.

In 2018, in collaboration with Xueping Ji, an archaeologist at Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, Bing Su at Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his colleagues successfully extracted ancient DNA from the skull. Given the warm and humid paleoenvironment at low latitude areas such as Yunnan, the success of recovering ancient DNA from MZR was a challenging task. Genomic sequencing shows the skull is a female. Although she has a unusual morphological characteristics, the team found she belongs to an extinct maternal lineage of modern humans, whose surviving decedents are now majorly found in the Himalayan region and Southeast Asia.

“Ancient DNA technique is a really powerful tool,” Su says. “It tells us quite definitively that the “Mengzi Ren” are modern humans instead of an archaic species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans despite of their unusual morphological features.”

The finding also shows during the Late Pleistocene, human populations living in southern East Asia had rich genetic and morphologic diversity, the degree of which is greater than that in northern East Asia during the same period. “It suggests that early humans who first arrived in eastern Asia had first settled in the south, before some of them moved to the north”, Su says.

“It’s an important piece of evidence for understanding early human migration” he says.

In addition, the team compared the MZR genome to that of people from around the world. They found that she linked deeply to the East Asian ancestry of Native Americans. She exhibits closer affinity to Native Americans than the Ho?abi?nhians (from Southeast Asia), Jomons (from Japan), as well as the Paleo-Siberians (beyond 20 kya) and Tianyuan (from Zhoukoudian) does. Based on this pattern of genetic affinity, they inferred that ~16,000 to 14,000 years ago, from Maludong in the south to the Amur region in the north, the broad Late Pleistocene East Asians already formed an ancestral clade that directly contributed to the First Americans. Combined with previous research data, the team proposed that some of the southern East Asian people had migrated northward along the coastline of nowadays eastern China, by way of Japan, reaching Siberia, and eventually crossed the Bering Strait between the continents of Asia and North America, and became the first group of people arrived in the New World.

By looking at the spatial-temporal distribution of an East Asian specific sequence variant, which causes skin lightening in current East Asian population. They found that this variant first appeared in the southern coastal region of China during the early Holocene (~7.5 kya), and it quickly elevated to high frequencies in northern populations due to natural selection on skin pigmentation.

Next, the team plans to sequence more ancient human DNA using fossils from southern East Asia, especially ones that predated the Red Deer Cave people in order to elaborate the migratory and diversity patterns of early modern humans in eastern Asia.

“Such data will not only help us paint a more complete picture of how our ancestors migrate, but also contain important information about how humans change their physical appearance by adapting to local environments overtime, such as the variations in skin color in response to changes in sunlight exposure.” Su says.

Funding information: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the Kunming Institute of Zoology, CAS, Yunnan provincial “Ten Thousand Talents Plan-Youth Top Talent” project, and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS.

The skull of Mengziren (MZR) unearthed from Red Dear Cave (left: anterior view; right: lateral view)

(Image by : Courtesy by Xueping Ji and Mengzi Institute of Cultural Relics.)

The excavation site of Maludong (Red Deer Cave)

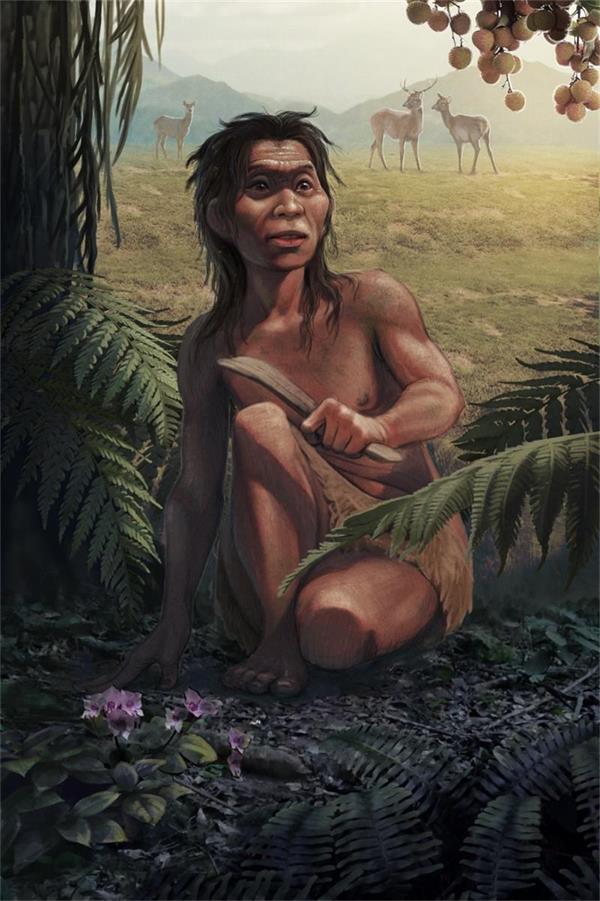

The reconstruction of Mengziren (MZR) and her living environment, courtesy by Kunming Institute of Zoology, CAS

(Image by : Courtesy by Xueping ji)

(By SU Bing, Editor:GAO Yuan)

Contact:

SU Bing

sub@mail.kiz.ac.cn