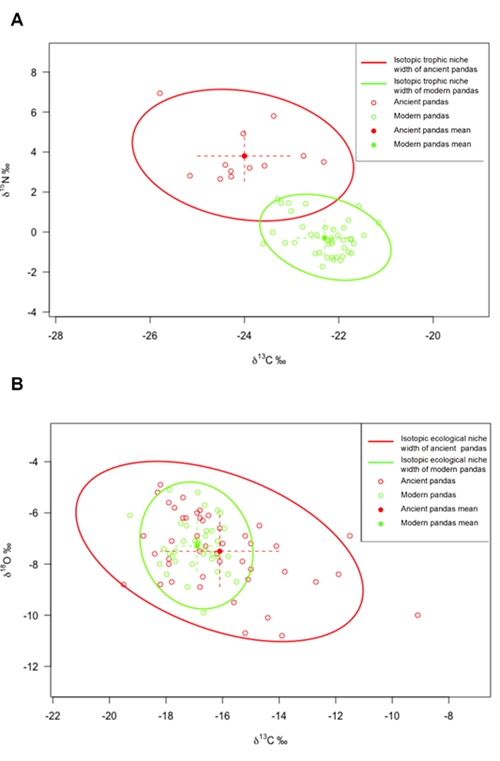

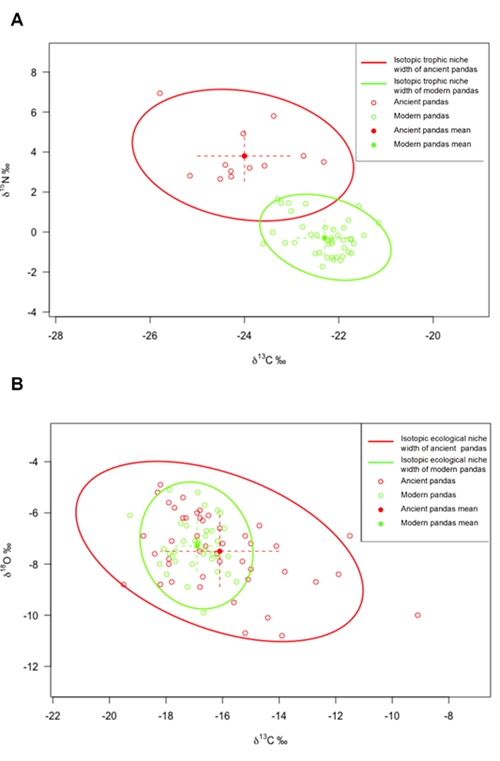

Today, giant pandas are represented by one iconic species, Ailuropoda melanoleuca, and live only in the understory of particular mountains in southwestern China. The ancestral panda Ailurarctos lufengensis excavated at the Shihuiba site in Lufeng, Yunnan from the late Miocene (7-8 Myr), is thought to have been carnivorous or omnivorous. The first chronospecies in the genus Ailuropoda, the pygmy panda (A. microta), emerged in the late Pliocene and is thought to have been a specialized bamboo feeder.Records show that A. microta and later A. baconi (always found in abundance among Ailuropoda-Stegodon fauna during the Pleistocene), had a widespread distribution and occupied different habitats over southern, central and northwestern China that extended as far north as Beijing and as far south as Myanmar, northern Vietnam, Laos and Thailand.The giant panda possesses a carnivore-like gastrointestinal system, suggesting that its ancestors ate a meat diet. However, it now consumes almost exclusively bamboo (99%) and has distinctive teeth, skull and muscle structural characteristics related to crushing and grinding fibrous food.The morphological characteristics of teeth for giant panda have adapted to consumption of tough, fibrous bamboo during the long evolution from the carnivore-like ancestral Lufeng panda to the living panda. A special feature, an exaggeration of the radial sesamoid (pseudo-thumb), has evolved to permit the precise and efficient grasping of bamboo. In contrast to extant pandas, little is known about the diet and habitat of extinct pandas. Paleontological and molecular evidence suggest that pandas switched to bamboo feeding ca. 2 million years ago, however, the first description of their bamboo diet is only a few hundred years old.Although morphological and functional anatomical studies on panda fossils have speculated on habitat and dietary preferences, there is little direct evidence. Pandas now survive in a fraction of their historical habitat, but no specific information has been reported.Stable isotopic analysis are used to study dietary shifts and trophic and ecological niches in humans and other animals. Isotopic signals can record dietary changes between modern and historical populations. Because of the poor resistant ability of bone collagen to post-mortem diagenesis, teeth enamel isotopes are a better choice for determining dietary shifts and ecological implications over long periods of time, and have been used to investigate dietary variability, feeding changes, climatic features and habitat types in human and non-human animal evolution.As one of the earliest teams focusing on giant pandas study, the Research Group of Animal Ecology and Conservation Genetics led by Dr. Fuwen WEI from CCEAEG / Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, together with collaborators,recently investigated stable carbon (13C/12C) and nitrogen (15N/14N) isotope ratios in bone collagen, and carbon and oxygen (18O/16O) isotopes in tooth enamel from extinct and extant pandas and contemporary sympatric carnivorous and herbivorous mammals.The study is published online in Current Biology on Jan 31.Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios in bone collagen from ancient pandas, modern pandas and sympatric species indicate that the trophic niches of ancient and modern pandas are distinctly different. According to SIBER model analysis, the isotopic trophic and ecological niche widths of ancient pandas are approximately three times larger than those of modern pandas. This suggests that ancient pandas might have a more complicated diet and were not obligate bamboo feeders, and they probably adapted to a variety of habitat types, such as forest fringes, subtropical zones and open land, other than dwelling in bamboo forests as they do today.The researchers suggest that pandas' dietary habits have evolved in two phases. First, they suggest that the pandas went from being meat eaters or omnivores to becoming dedicated plant eaters. Only later did they specialize on bamboo.Examining trophic and ecological niche widths via extinct and extant populations provides direct evidence of dietary specialization and habitat contraction in giant pandas, and improves our understanding of their adaptation to modern environments.This work was supported by Strategic Priority of the Chinese Academy of Sciences the National Key Program of Research and Development, Ministry of Science and Technology, the Key Project and Creative Research Group Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China.(Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

Wild Giant Panda in Foping Nature Reserve, feeding on bamboo (Image by WEI Fuwen)

SEAB representation of isotopic niche width that is a bivariate equivalent to SD in univariate analysis of ancient (red) and modern (green) giant pandas. (a) δ13C and δ15N of bone collagen from pandas are used to construct ellipses indicative of ancient (red) and modern (green) trophic niche widths. (b) δ13C and δ18O of tooth enamel from pandas are used to construct ellipses indicative of ancient (red) and modern (green) ecological niche widths. Dots and dashed lines are means and standard deviations (SD) of ancient (red) and modern (green) pandas. (Image by WEI Fuwen) (Editor: RAO Fangfei) |